The Practical Better Rules Workshop Manual

Author: Hamish Fraser (@verbman), Service Innovation Lab, NZ

#BetterRules, #RulesAsCode

Version: Draft-02

Sections

- Very Important Foreword

- The Team

- Props

- Workshop Preparation

- Overview of the Outputs

- Getting Started

- The Process

- Developing the Rules

- Questions & Question Flows

- Service Design Research

- Process Flows

Very Important Foreword.

Consider this document a starting guide. It’s a methodology we’ve developed based on experiments that were conducted in the Service Innovation Lab in New Zealand. Do not treat this document as authoritative; instead use it to get your team and workshop started and then adapt to suit.

The key component is the multidisciplinary team. Policy and rule development has generally been isolated from implementation and this idea of getting everyone in the room is at the heart of “Better Rules”.

Each of the outputs represent large academic fields with complex and intimidating terminology so use these outputs as tools and keep your focus on using them at the depth you require to achieve better rules. Rules for humans should be approachable and understandable and so should the methods used to develop them.

The Team.

(Aim for approximately nine people)

- 1-2x Subject Matter Specialist

- 1-2x Policy Advisor

- 1-2x Legal Advisor &/or Legal Drafter/Parliamentary Counsel Representative

- 1-2x Rules-as-Code Specialist

- 1-2x Service Designer

- 1-2x Business Rules Specialist

Props.

- Comfortably sized room

(This could be tackled by a remote team however fluid communication is essential so internet connections would need to be up to the task.) - 2-3x Whiteboards

- Post It Notes

- Coding environment for rules-as-code specialist

- 2x Large screens

- 2x Computers (for business rules and rules-as-code specialists)

- Camera (for photographing whiteboards)

- A clear understanding of what “the domain” is the group will be focusing on.

Workshop Preparation.

A guide to how each team member should prepare for the workshop.

Subject Matter Expert.

Prepare an initial presentation on the domain for the team with the goal of giving the other team members a broad understanding of the history and challenges in the space.

Policy Advisor.

Ensure a good understanding of the current and historic policy positions as they relate to the domain is on-hand for them to supply the team

Legal Advisor.

Ensure a good understanding of the current and historic legal context to the subject matter are available to the team.

Rules-as-code Specialist.

Have previous to the project ensured they have a suitable coding environment (with test suite) setup ready to go and an understanding/experience in the process of coding rules. They will also need to have a methodology that non coders can utilise to create and store the tests.

Service Designer.

Establish a good understanding of the service design implications currently faced in the scope of the domain and prepare a simple report outlining what works and doesn’t work.

Business Rules Specialist.

Bring existing knowledge of business processes and rules and be prepared to present this perspective to the workshop.

A Brief Introduction to the Outputs.

A brief introduction to each of the outputs. Outputs are marked as either base requirements or optional outputs. Choosing which outputs are focused on will be dependant on the context and purpose of the workshop. The outputs could be incorporated into the enveloping institution’s documentation and kept as foundational reference material for the rules that have been brought into effect.

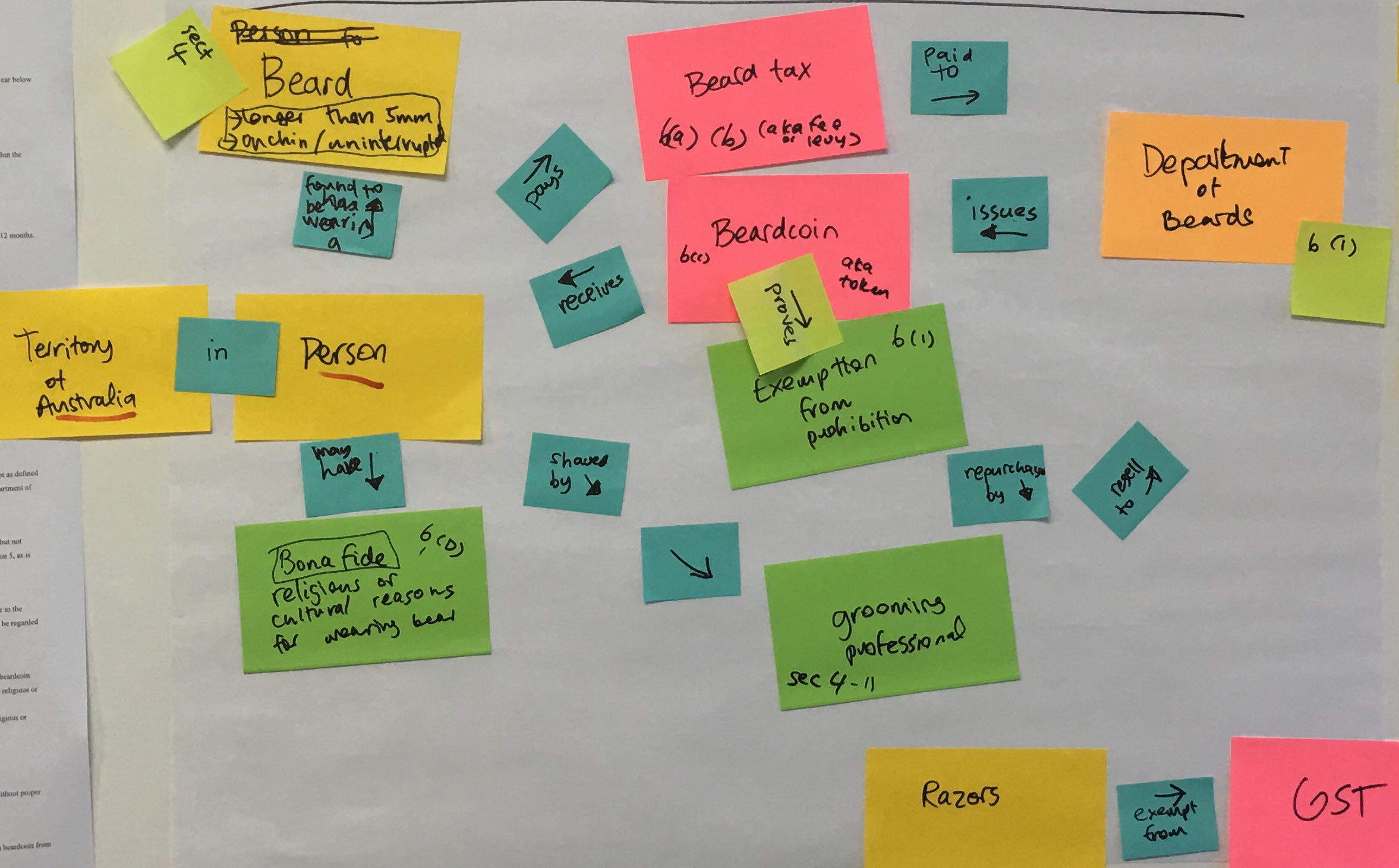

Concept Models.

[base requirement]

Concept models form a working map of the concepts that make up the domain the team is focusing on and are the essential central component to the workshop’s process. They allow the team to create a visual shared understanding of the domain and its scope, and it becomes a reference point that allows all the other expected outputs to achieve a high level of consistency. It is also the central mechanism for quantifying and resolving disagreements and differences in perspective and as such is constantly evolving and improving over the lifetime of the workshop.

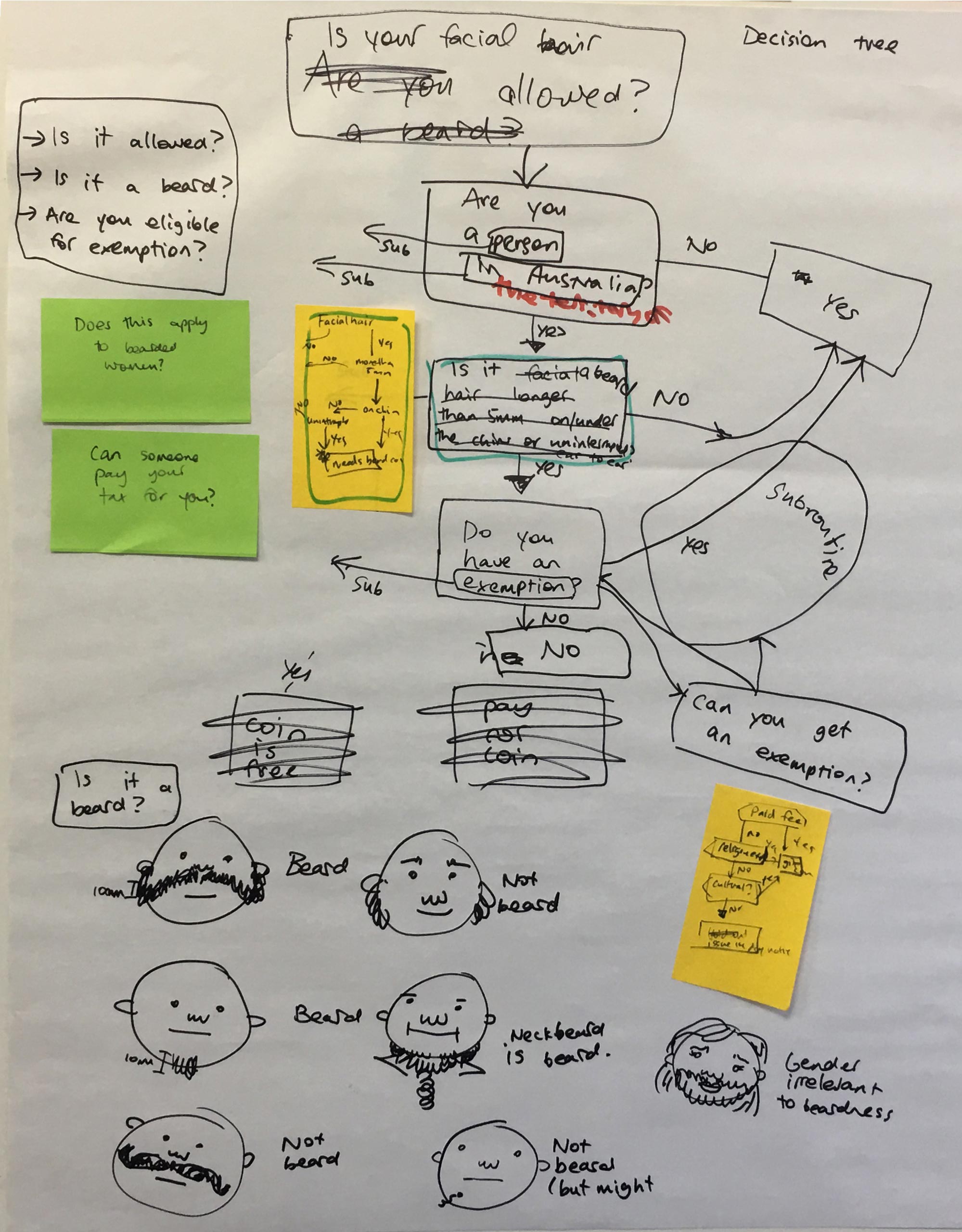

Decision Trees.

[optional output]

Decision trees map the logic and ways people and systems practically navigate the concept models. Experience suggests these maps can take anywhere from a few minutes to several days depending on the complexity of the concept model and the more complex ones will be revisited often in the same manner as the concept model. Their development will often result in changes to the concept model.

Business Rule Statements.

[base requirement]

Business rule statements are precisely written statements of logic describing each rule in a set of rules succinctly. An example might look like:

“A person is eligible to vote if:

- their age is 18 years or more, and

- they have lived in the district for 6 months”

Business rule statements are useful for both drafters and coders in establishing statements of logic. Note their dependency on the terms used and how they map to the concept model.

Rules-as-Code.

[base requirement]

Rules-as-code are best thought of as an opportunity to test the policy by trying to explain it to a computer. A phrase coined in response to this practice is:

“You haven’t really understood your policy until you’ve successfully explained it to a machine”.

The underlying explanation as to what happens in this process is the machine acts as an utterly unassuming context-free entity that by its nature aids in the discovery of assumptions that we miss much more easily as humans. This process on it’s own is enough to warrant undertaking the creation of this output however once the rules are written there are many other uses for them.

This is both a very new and old field of computer science so keep an eye on the #rulesascode hashtag to stay up to date with best practice.

Test Suites (aka Policy Intent).

[base requirement]

Test suites are an adoption from the world of software development. Think of them as capturing and preserving policy intent. A test is a description of a scenario with given inputs and what the expected output(s) should be. Couple this concept with rules-as-code and it’s possible to write thousands of tests for all conceivable scenarios and leverage computers to run those tests in an automated fashion. They provide an easy bridge for non programmers to engage with the coding aspect of rules-as-code by being involved in the writing of the tests and studying the results.

Questions & Question Flows.

[optional output]

Question flows inform the impact rules will have on the types of problems Service Designers focus on. Specifically they provide insight into the complexity and logic that the rule set demands in the form of questions that need to be answered to process the rules. An example might be a rule that states “the height of the building cannot exceed 10 metres”. This prompts the need for a question “What is the height of the building?”. These questions are often hierarchical and whether they need to be asked is dependant on the answers to previous questions.

Service Design Research.

[optional output]

An extension to the question flows is the consideration of the impact the ruleset has on delivery of services that might be attached to the ruleset. Service designers can provide an analysis of the rules and model the impact they will have on services and people’s access to them.

Process Flows.

[optional output]

Process flows are detailed flow charts of the process(es) that will be required to support the rules. They are especially useful in questioning how implementable a ruleset is and can provide insight into bottle necks or inconsistencies that the rules might introduce. Keep in mind there is often multiple process flows for a set of rules depending on the perspective and roles of the people the rules affect.

Getting Started.

The goal of the multidisciplinary team is for each member to feed into the group their specialist knowledge of the domain in as much as is possible so all the knowledge is shared and the solution can be focused on collectively. The key mechanism for tracking the progress and representing the shared knowledge of the group is the concept model. The concept model is the central foundation for all work undertaken by the team for the length of the workshop and will be covered in more detail in the section “How to Concept Model”.

Objectives.

Be clear with respect to the objectives of the group. This will be one or a combination of the following.

- Understanding, mapping and coding the existing rule space

- Clarifying and clearly stating the policy intent

- Modifying or adding to the existing rule space to match the policy intent.

Team Dynamics.

Ensure each member of the group is comfortable in sharing their perspective and confident in disagreeing/questioning the rest of the group; this team dynamic is important for ensuring success. If the team are new to each other it’s advisable to set aside time to foster a sense of trust and undertake some team-building/ice-breaking activities.

Once this has been achieved the team is ready to start.

The Subject Matter Expert should open with their pre-prepared presentation on the topic. This introduction is a good time to set the scene and declare the objectives of the exercise so the Policy roles will likely co-present.

How to Concept Model.

Work should start immediately (during the initial presentation) on developing the Concept Model and can be facilitated by other team members.

The Concept Model is initially a messy process and one should keep in mind its purpose. The overriding role of the concept model is to provide a focal point that allows the group to form a shared consistent view of the domain.

Expect it to be redrawn multiple times and plan accordingly. Post-it notes directly to whiteboard is not a bad starting approach for this reason. Utilise the whiteboard to draw connections. Connections can be labelled. Do not get distracted by logic flows, that comes later. As the above example shows: beard and “beard tax” are identified as concepts - they are then linked with the concept “person” - the word used in the current rule set. Age is also identified and posted close to “claimant” as it applies to that concept.

Expect a sense of agreement to develop within the group and for that to be suddenly interrupted by disagreement, repeatedly. The concept model provides a focal point to work out disagreements in how the model is perceived and will be modified often as part of this process. This is the concept model fulfilling its purpose.

Creating an “out of scope” section can help keep the group in agreement on the scope of the project and remind people of what has been previously discussed and ruled “out of scope”.

The Process.

Once the concept model is underway and team members believe it’s reached a level of maturity and clarity which they’re comfortable with - a number of other activities which contribute to the output of the workshop (described below) can be added to the group’s work flow.

Focus the individual team members as outlined below on their appropriate tasks but to try and work through the process as a collective, sharing into the wider group the questions inspired by their respective tasks. Each of the tasks is likely to throw up new insights and changes to the concept model - and these will need to be absorbed and discussed by the whole team. Iterative over each of the rules individually so each task has an opportunity to interrupt and inform the other parts of the team while they are looking at the same components. While this feels somewhat slower, it allows the group to be giving full consideration to each point as they move through the processing of the tests, rules and service modelling impacts which will often result in a more thorough and ultimately more efficient process.

It’s essential that the group keeps checking in as a whole to discuss findings as is appropriate to the process.

Developing the Rules.

Note this activity can differ a little depending if existing rules are being unpacked or new rules being written or both. Regardless, it’s important to keep the rules tied directly to the concept model which is the group’s shared understanding of the domain. This is best done by ensuring the terminology used is kept consistent.

The process for new rules starts with the Policy Advisor giving an outline of the proposed new rules from their research in the domain. Each of the team will likely have perspectives to share on what’s proposed.

Each of the outputs of the workshop are designed to highlight gaps and inconsistencies in the rules. It’s often helpful in analysis of the rules to play with “what-if” statements that focused on changing variables that are often assumed.

For example, what if the:

- location (i.e. not in the country)

- timing (change the order of events)

- role (the caregiver is a child)

- classification (they are not citizens)

is X and does our ruleset account for that. This is a useful practice to apply during the development of the test suites which we will detail shortly.

Developing Decision Trees.

Suggested Roles: [Legal Advisor, Business Rules Specialist, Service Designer, Rules-as-code Specialist]

A decision tree is created by taking the elements of the concept model and organising them in an order that represents the sequence (if there is one) that people and systems would use to navigate the process. They provide the opportunity to look at the logic dependencies that exist in the domain. It provides another way to describe the domain and will often highlight inefficiencies in the approach and inaccuracies in the concept model.

Wikipedia entry for decision trees

Developing Business Rule Statements.

Suggested Roles: [Business Rules Specialist, Legal Advisor]

The business rules specialist keeping the concept model in mind, starts the process of crafting the statements that make up the individual components of logic within the domain. Keep in mind the order of these is often related to the decision trees. It’s important to try and keep each line or statement precise and describing a single point. Wikipedia entry for business rules

Developing Rules-as-Code.

Suggested Roles: [Rules-as-code Specialist, Legal Advisor]

While coding the rules, it’s expected that the rules-as-code specialist keeps an eye on the underlying concept model and any assumptions they may find themselves making while developing the code should be raised. The art of coding rules is to be very careful to not include any assumptions or extensions of logic accidentally into the code but faithfully mirror the rules in an isomorphic fashion.

Example uses for rules-as-code:

- Enables the use of test suites

- Provides a workable implementation model of the rules.

- Offers a chance to publish the code in a similar manner to how legislation as text is published (such as in New Zealand).

- Provides an opportunity for modelling the effects of the rule set in conjunction with existing datasets building on top of such concepts as the “digital twin”.

Test Suites.

Suggested Roles: [Subject Matter Specialist, Policy Advisor, Rules-as-code Specialist]

The rules-as-code specialist will need to advise on the format for the tests (a spreadsheet can be a low tech solution) so they can later be converted into code and run against the rules-as-code output. They should also be relied upon to give an introduction to test writing, documentation requirements and good practice.

Writing tests is initially an exercise in expressing the policy intent but then switches to an exhaustive analysis of possible scenarios. If the rules-as-code specialist is not yet sure of the format of the tests, the scenarios can be described in spreadsheets ready for importing alongside the code.

Questions & Question Flows.

Suggested Roles: [Service Designer, Business Rules Specialist, Rules-as-Code Specialist]

#Todo

Service Design Research.

Suggested Roles: [Service Designer, Subject Matter Expert]

#Todo

Process Flows.

Suggested Roles: [Business Rules Specialist, Service Designer]

#Todo